Article: A sneak preview of Musenki’s new wireless access point

Apr 12, 2002 — by LinuxDevices Staff — from the LinuxDevices Archive — 15 viewsBack in November of 2000, Jim Thompson, Kem McClelland, Brad Martin, and Jamie Thompson started brainstorming about the idea creating a company to specialize on the emerging market for publicly accessible wireless access points. They reasoned that there would soon be a significant opportunity to supply devices to public access “hot-spot” providers, wireless ISP/infrastructure providers (WISPs), and… various value added resellers (VARs).

Thompson and McClelland were both senior managers at WapPort, where they had both been frustrated by the inability to convince existing access point providers to modify their products for “hot-spot” features, or even to allow Wayport to have access to their source code so that Wayport could make the necessary modifications. So the two, joined by Brad Martin and Jamie Thompson, decided to have a go at it on their own.

“My original frustration when I was at Wayport, was that we couldn't get any of the existing access point manufacturers (Cisco, Lucent, Symbol, etc) to embed the features we needed to deploy an 802.11-based “Hot Spot” service,” recalls Musenki CTO and founder Jim Thompson.

Roughly 18 months later, Austin, TX based Musenki (“musenki” means “small wireless gadget” in Japanese) is poised to ship beta units of its first product — the M-1 wireless access point. The devices, which are scheduled to ship to customers next Monday (April 15, 2002), will be sent to developers, strategic technology partners, VARs who want to start integrating their own features, and some prospective major customers. Among the significant customer prospects being sent beta units are several regional wireless ISPs and mobile operators, according to McClelland.

McClelland describes Musenki as a developer of “secure, open-source wireless networking products” whose “software and high-performance equipment enable open development, bringing expandability and customization to the wireless LAN market.” Indeed, the company's first device packs a lot of computing power in a very small space, by taking advantage of some of Motorola's highly integrated PowerPC-based system-on-chip processors running at speeds ranging from 200 to 400 MHz, along with high density RAM, built-in solid state disk (Flash memory), and internal expansion based on “miniPCI” modules. The use of built-in PCI expansion allows Musenki to configure its access points for a variety of wireless interfaces — an important factor in an emerging technology-based market that has a long way to go before stabilizing.

According to McClelland, Musenki has incorporated several features into its wireless access points that are crucial to success in the public access market. These include tie-ins with external authentication and billing systems, roaming across various service provider networks, the ability to slot-in additional network-layer functionality such as VPN and protocol translation, and functions that enable the management of a large number of these devices disbursed over a large number of locations.

What's on the drawing board after the M-1 and M-3 wireless access points have made it into full production? According to McClelland, Musenki's plans include a number of technology and interface enhancements and upgrades, including . . .

- Client side devices (miniPCI/PC cards, particularly GPRS/802.11 combo cards)

- Mesh networking technology

- Technology for enabling seamless roaming, by means of cellular and WLAN networks

- Additional security features

- Integration with innovative antenna technologies

- Expansion of the platform beyond the WLAN market

Building in power and flexibility

Jim Thompson characterizes Musenki's first product as a Linux-powered 802.11 access point: “Its open, so the customer can make it do what they want” So flexible, in fact that you could use it for other things. “Like a sexy small, high-performance router,” according to Thompson. “Take the 802.11b NIC out and install one of several available miniPCI modules with crypto/compression chips, and now you've got a VPN router — with compression — that will run at 100Mbps.”

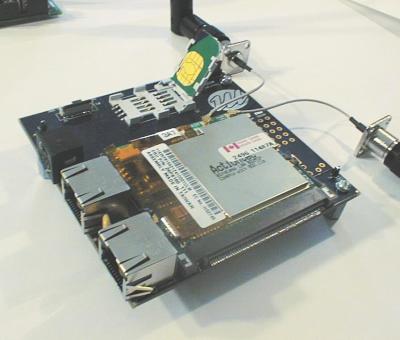

Prototype of the M-1 access point

Here is a summary of the features of the embedded computers that are built into the M-1 and M-3 . . .

M-1 specs . . .

- Processor: Motorola MPC8241 running at 200MHz

- RAM: 32MB (default), 64MB, or 128MB of SDRAM

- Flash: 8MB (default) or 16MB

- 1 x Davicom DM9102AF (tulip-clone) 10/100 Ethernet on RJ45

- 1 x miniPCI socket (comes filled with a 802.11b NIC and “AP” software)

- miniPCI socket has the pins for V.90 modem and 10/100 Ethernet brought out to a second RJ45

- 1 x Smart Card (SIM form-factor)

- I2C header

- 3.5 x 3.6 in. (smaller than PC/104 form-factor)

M-3 specs . . .

- Processor: Motorola MPC8245 running 333MHz

- RAM: 1 x SODIMM socket, usable with up to 512MB (off-the-shelf modules)

- Flash: up to 32MB

- 2 x Davicom DM9102AF (tulip-clone) 10/100 Ethernet on RJ45s

- 2 x miniPCI socket

- first slot comes filled with a 802.11b NIC and “AP” software);

- first miniPCI socket has the pins for V.90 modem and 10/100 Ethernet brought out to a second RJ45

- first slot comes filled with a 802.11b NIC and “AP” software);

- 1 x full PCI slot (more Ethernet, T1, T3, additional 802.11a/b/g NIC, etc.)

- 1 x Smart Card (SIM form-factor)

- I2C header

- Size: 6.0 x 7.0 in.

Closeup of the M-1's internal single-board computer

“We feel that the additional CPU and the large memory resources are going to be more and more important as 802.11x (x = a, b, g) becomes the predominant method of client connectivity,” points out Thompson. “In addition, as other 802.11 standards mature — for example 802.11e Quality of Service, 802.11i security, 802.11f Inter Access Point Protocol, 802.11h Dynamic Frequency Selection (DFS), and Transmit Power Control (TPC) — we will have the CPU power and architecture to allow us to incorporate these improvements, as well as the future increased bit-rates planned for 802.11a.”

“Also, the minute you start thinking about 'mesh' routing, you need lots of memory and CPU resources,” Thompson adds. “Consider a medium-sized city with 40,000 houses, all connected to each other via a wireless 'fabric' at 20Mbps or more.”

“One could run an 802.11b (or 802.11g) NIC in one slot and an 802.11a NIC in the second slot and have a 'dual-mode' AP, with all the gateway features still enabled,” explains Thompson. “Or you could use all three slots — one slot of 802.11b for older clients, one slot of 802.11g for those clients, and one slot 802.11a. Or you could cover a coffee shop with 802.11b/802.11a and still bring a DSL, Cable, or T1 connection or even 802.11 'back-haul' out with one box, AND run the 'captive portal' on the same box.”

Thompson explains that there are varied reasons for the Smart Card. “One of the most interesting is that if you're going to deploy this type of equipment into 'public access' venues, you need a way to both secure the contents against prying eyes — and people who will dredge through your Flash — as well as being able to potentially authenticate the equipment back to your billing system, if you're Wayport, Surf-n-Sip, VoiceStream/Mobilestar, Boingo, etc. We use the smart card for both of these, and more. Consider the use of Smart Cards in GSM phone or DBS satellite systems, and then apply same ideas here.”

Embedded Linux inside

Musenki's wireless access points run a recent version of the Linux kernel (currently 2.4.18), along with other open source software.

“For Linux, we started with the PowerPC kernel sources from BitKeeper,” says Thompson. For the bootloader, for example, they started with ppcboot sources and added 8245 support. “We've given all the code back to the community. Interestingly, I ended up supporting the 'Sandpoint8245' platform in the process.”

“We did it all ourselves, with more than a bit of 'help' from the associated mailing lists,” continues Thompson. “Linux mostly just 'runs', other than small bits of effort to get the on-chip serial ports working, and board-specific issues.”

Why Linux?

“We see open source software as our greatest strategic advantage,” says McClelland.

“Essentially, Linux lets us do what we want to do, because we have source — stand on the shoulders of giants, and not pay royalties to Wind River,” Thompson adds.

The development process wasn't without its “bumps in the road”, explains Thompson. For example, the time he discovered that the Flash memory bus was wired backwards on the 'BBWISP' board. “This is one of the places where 'open source' ruled for us, because I just hacked support in for changing the 'endianess' of the Flash bus to an existing driver for the Flash chip we're using,” he adds.

Thompson claims it took him about half a day to solve the Flash bus problem, thanks to the availability of Linux source code. “I can't imagine having to do that on VxWorks,” he says.

According to Thompson, the following open source projects were valuable to Musenki in the development of its wireless access point products . . .

- PPCBoot

- PowerPC Linux kernel

- Busybox

- hostap

- uClibc (A glibc2 environment is also available)

- M.U.S.C.L.E (Movement for the Use of Smart Cards in a Linux Environment)

- open1x.org

How will they cost, and how will they be sold?

Quantity one pricing for the M-1 (including 802.11b NIC, antenna, power supply, etc) will be $300, and the M-3 (similarly configured) will be $500, with quantity discounts available.

Beta units of the M-1 will go out on Monday, April 15th. Beta shipments of the M-3 are planned by the beginning of May. General availability of both should be by the end of June.

Initially, the units are being sold directly by Musenki, but the company is currently developing various sales channel relationships.

What's next for Musenki?

Musenki is currently staffed by six people (four founders plus a hardware and software engineer), along with consultants and part-time employees who have contributed to the open source, open architecture approach. Musenki is self-funded to date and is actively discussing additional financing with outside investors.

This article was originally published on LinuxDevices.com and has been donated to the open source community by QuinStreet Inc. Please visit LinuxToday.com for up-to-date news and articles about Linux and open source.