IBM’s 90nm phase-change memory tech unveiled

Jun 30, 2011 — by LinuxDevices Staff — from the LinuxDevices Archive — 4 viewsIBM says it has produced 90-nanometer-size processors that can store multiple bits of data per cell over time without the data becoming corrupted. The multi-level phase-change memory (PCM) technology should lead to solid-state chips that can match NAND flash disks' 1TB capacities, but are about 100 times faster and feature a much longer lifespan, claims the company.

Every so often, the IT world gets news of a "breakthrough" in new storage media research. This week it was IBM's turn to announce one in relation to a possible long-term replacement for NAND flash solid-state disks.

Big Blue on June 30 revealed that its Zurich-based phase-change memory (PCM) research unit has produced 90-nanometer (nm) sized chips that can store multiple bits of data per cell over time without the data becoming corrupted. This appears to be the solution to a problem that has been nagging PCM development since IBM started this project nearly 10 years ago.

NAND flash is inherently slowed down by so-called erase-write cycle limitations. This is because NAND flash requires that data first be marked for deletion before new data is written to the disk, which slows the process considerably.

PCM does not require erase-write cycles. Thus, the extra erase-write activity causes NAND flash performance to degrade faster and, over time, wear out the disk.

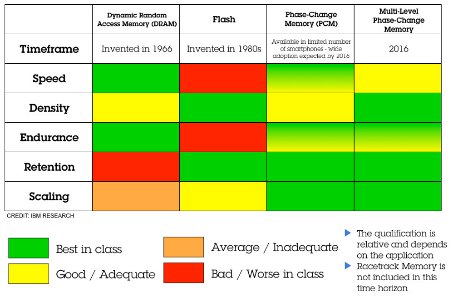

IBM chart showing advantages of multi-level PCM, expected to be commercially available in 2016

Source: IBM

(Click to enlarge)

Typically, NAND flash disk lifespans range from 5,000 to 10,000 write cycles in consumer disks and up to 100,000 cycles in enterprise-class disks. In contrast, PCM can handle up to an estimated five million write cycles, contend both IBM and PCM player Intel, the latter by way of its PCM-dedicated Numonyx arm.

Whole new world of storage?

With endurance of that nature, both companies believe that a whole new world of computing and data storage could be no more than about five years away.

A phase-change memory chip — also known as PRAM — is nonvolatile memory that works well for both executing code and storing large amounts of data. This gives it a superset of the capabilities of both flash memory and dynamic random access memory. As a result, it can execute code with performance, store larger amounts of memory, and also sustain millions of read/write cycles.

Intel debuted its first PCM chips at its developers' conference in San Francisco in September 2006. Both Intel and IBM have been working on this for more than a decade. The wafer shown to eWEEK that day represented Intel and Italy's ST Microelectronics' first grasp of the new type of nonvolatile memory chip. The two companies later merged to create Numonyx.

A great deal of development has been completed at IBM and Numonyx in the last five years. In October 2009, Intel and Numonyx announced a "key breakthrough" in PCM development, having created a 64Mb test chip that demonstrated the ability to stack multiple PCM arrays within a single die. The month before, Samsung announced that it had begun producing 512Mb (64MB) PRAM chips claimed to be up to ten times faster than flash while extending handset battery life by more than 20 percent.

Numonyx CEO Ed Doller told eWEEK that the adoption by mainstream IT companies has been slow, but that it would take use only a couple of big names — Apple and Microsoft would be two of them — for PCM to take off into the market stratosphere.

"PCM is on the verge, and we think it's inevitable that it will replace a lot of what is in devices today," Doller said. "But to start, it would take a company that is good at producing both hardware and software to make best use of it. It's bound to happen."

Doller thinks PCM will need a few more years to attain widespread adoption. Right now, the biggest drawback in PCM is the price, which is about 10 times higher than DRAM at this point. The pricing, however, will come down over time and as fabricating processes become improved.

Chris Preimesberger is a writer for eWEEK.

This article was originally published on LinuxDevices.com and has been donated to the open source community by QuinStreet Inc. Please visit LinuxToday.com for up-to-date news and articles about Linux and open source.