Article: The little Linux chip that could

Jan 26, 2001 — by Rick Lehrbaum — from the LinuxDevices Archive — 2 viewsOne year ago, Palo Alto, CA based “ZF Microsystems” changed its name to “ZF Linux Devices” and began promoting an interesting new system-on-chip processor called the “MachZ” as a Linux-oriented silicon device. Why did ZF decide to focus itself on Linux — to the point of a change in corporate name?

David Feldman, ZF's founder and CEO, says he first began noticing a growing interest in Linux among his company's embedded market customers three years ago. Although he considers the absence of Linux software royalties to be a key factor, Feldman thinks an even more significant issue motivating developers to use Linux is the unrestricted access they have to Linux source code. Embedded market customers often complain of proprietary OS vendors' unwillingness to provide source — whether for supporting the development project itself, or for use in gaining regulatory agency approvals.

Now that Linux is ZF's middle name, Feldman reports that as many as 85% of ZF's customers begin their development projects with plans to use Linux as their embedded OS. That percentage drops to 60-70%, once reality sets in, since some customers run into device driver issues, or are disappointed to discover that Linux doesn't offer the user-friendliness of Windows. To accommodate the remaining 30-40%, ZF recently reached an accord with proprietary RTOS vendor Wind River, whereby a VxWorks license will be bundled with every MachZ chip.

What's in a MachZ?

The device is a system-on-chip based on a Cyrix “586” CPU core and fabricated by National Semiconductor. It's implemented on a single die that includes the CPU, cache memory, PC core logic, boot ROM, I/O functions, “north bridge” (PCI bus interface), “south bridge” (ISA bus interface), and DRAM interface. To help minimize costs, the MachZ's DRAM interface supports both 32- and 16-bit data widths, which makes it possible to design a working system that needs just one DRAM chip. Additional technical details are available here.

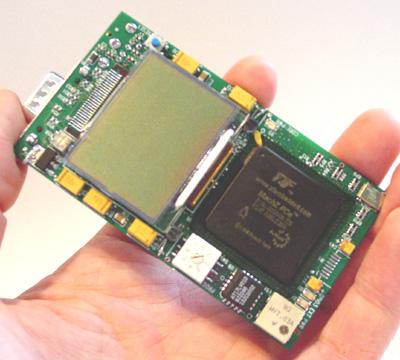

The MachZ tiny demo board

What's next in the MachZ product family? “We're currently working on several different MachZ companion chips that contain interface functions targeted at specific markets,” says Feldman. “Things like GPS, Bluetooth, and so on.”

The company is also in the process of implementing a die shrink from 0.25 µ to 0.18 µ, which is expected to increase the MachZ's CPU clock rate from its current 128 MHz to 166-200 MHz. There's also a plan to offer the MachZ in a smaller 388-ball BGA (ball grid array) package. “And we're developing chip scale packaging,” adds Feldman.

David and the Goliaths

How can the MachZ compete with the many x86, RISC, and PowerPC based system-on-chip processors from chip manufacturing powerhouses like National, STMicroelectronics, Intel, Cirrus Logic, Motorola, and IBM?

“First, it's important to understand that we're not in a 'megaherz arms race',” points out Feldman. In fact, the MachZ's speed is often lowered by customers in order to reduce power consumption — all the way down to 238 milliwatts! Feldman says a common reason for using RISC and MIPS CPUs in the past has been due to the high power requirements of PC-compatible x86 processors. Accordingly, ZF publishes a chart that compares the MachZ's minimum power requirements with those of AMD's Elan400 (0.8W), Transmeta's Crusoe (1W), National's Geode GXLV (2.5W), and STMicroelectronics' STPC (4.2W).

Another strength of the MachZ, according to Feldman is that it's more generic than the “big company SOCs.” “Think of it as the Z80 of the next decade,” he says. For example, the MachZ is both versatile and easily interfaced, due to its simple glueless, non-multiplexed ISA and PCI expansion buses. “Where else can you get the assurance of a long term supply for the ISA bus?” asks Feldman. “We have customers for the MachZ who aren't willing to redesign their entire systems just because the ISA bus is being phased out of desktop/laptop PC chipsets.” Additionally, the relatively slow-speed (8 MHz) ISA bus makes it easier to minimize unwanted electromagnetic radiation in systems that can't tolerate EMI. Designing interfaces that work with the ISA bus is also less complex than with PCI.

Failsafe boot

Perhaps the most interesting feature of the MachZ — and one which ZF continually highlights — is its “FailSafe boot” capability. The reasoning goes like this: these days, nearly every embedded system uses Flash memory for its program storage — but the process of updating the system's operating software introduces the risk of ending up with a nonfunctional system, resulting in system down time and costly repairs.

To reduce this risk as well as that of several other types of system failures, ZF created a unique bootstrap loader program for the MachZ, which is contained in an on-chip 12KB ROM. The loader can supposedly bootstrap any BIOS and can also operate the system, to a limited extent, in case external Flash memory is empty or its contents have been corrupted. When necessary, the loader performs a series of steps that attempt to reload the contents of the Flash memory from several external sources.

One surprising capability, is the ability of the bootstrap loader to operate the system — albeit in a minimal manner — in the extreme case when both external DRAM and external Flash malfunction. How? The key to doing this, according to Feldman, is that the bootstrap loader runs its software from within the MachZ's internal 8KB cache memory instead of from off-chip system RAM. That allows it to perform diagnostic functions and report system failures in the absence of off-chip memory. It might, for example, call for help over a modem; or it could write a message like “Call 1-800-555-1212 for service” to a display device.

Chips, boards, or systems?

ZF sells a number of products besides the MachZ chip. These include several types of single board computers (in PC/104 and EBX form-factors), the netDisplay (an LCD computer subsystem), and the zPort PC home Internet appliance (offered in five colors). Which raises the question: what is the company's main business thrust — chips, boards, or systems?

The answer, says Feldman, is that the company is primarily focused on the MachZ. In fact, inspired by the open source nature of Linux, ZF is making its own “source” to just about everything — not including the design of the MachZ itself — available to its customers, in order to reduce development headaches, risks, and timeline. “We'll give you a CD with full schematics, board layouts, and even the enclosure design for the zPort PC — in short, we'll give away the entire manufacturing plans for a ready-to-build Internet appliance based on the MachZ.” ZF also provides the design documentation for the Ethernet and video controller cards that are used in the MachZ's development system.

What sort of success has ZF had with the MachZ so far? In the first six months since the MachZ began shipping, the company claims to have sold over 400 development systems and logged more than 100 design wins. “These are all in various stages of prototype development right now,” adds Feldman.

Win a MachZ!

ZF and the new Embedded Linux Journal magazine are cosponsoring a design contest. MachZ-based PC/104 boards with supporting material will be given to the submitters of the 100 most interesting project proposals. Those winners will then be entered into the grand prize competition, and the winning grand prize entrants in each of five categories will receive all expense paid trips to Costa Rica.

Please note: Subsequent to the publication of this article, ZF Linux Devices has changed its corporate name to “ZF Micro Devices” and the name of its MachZ SOC to “ZFx86”.

This article was originally published on LinuxDevices.com and has been donated to the open source community by QuinStreet Inc. Please visit LinuxToday.com for up-to-date news and articles about Linux and open source.